The stories we tell about peace and war have been top of mind these last few weeks with the release of the Wonder Woman movie and the adoption of the new UN treaty to ban nuclear weapons.

In one version of my feminist self, I celebrate the ovarian victories of this film. Wonder Woman was directed by Patty Jenkins, the first time a studio superhero movie has been directed by a woman. And it has entered the record books as the highest opening and highest-grossing female-directed movie, and the quickest and highest grossing movie in the DC Comics chain.

On set, the partners of the female actors with children tended to the kids, a fact commented upon in interviews about the making of the movie, and awesome as part of the shift away from a single primary care giver model (most commonly the mama).

But, in another version of my feminist self I am troubled by Wonder Woman and the stories it tells of love, war, violence and peace. And I don’t really love the ways in which other women in the film are represented.

To that latter point first. And I’ve got to preface this by saying that I am not a comic book gal. Lovely folks who are have talked with me about the ways in which this movie and the comic recasts some dominant tropes, and so that is awesome and a victory – cause we want strong, awesome women in comics. But, how amazing would it be to have a kickarse superhero without a cinched waist?

It does also bother me that the two other major roles for women in the bulk of the movie trot out some pretty boring physical tropes. Facial disfigurement is one of the markers of evil for Doctor Poison (all very Dorian Gray, so it’s not just gendered, I get that). But in the context of women and the strictures of beauty that constrain our lives it sucks that the movie trots out a version of Doctor Poison that runs with the facial disfigurement approach – other versions have her in a simple eye mask with no facial disfigurement. (I also get that masks are all very big in comic land!)

And then there’s Etta Candy, the sidekick role, who is most commonly a larger woman than WW. And so that’s complicated again, right? So, awesome that there are a diversity of body types and Lucy Davies talks about how great it was to not hold her tummy in for filming. And I understand that the sidekick role is often light relief. But there is also a cultural norm that has us more comfortable when women who don’t fit the skinny model become acceptable when they are funny.

So to the stories of love, war, violence and peace, masculinity and femininity. At the outset, I understand that comics are modern-day morality stories, and so exist more in the binary of good/evil, albeit in a continuum state where good often also explores the ambiguity of means and ends. It was probably obvious that I was going to have some issues with WW: when I came out of the movie with my friends we did have a moment where we looked at each other and laughed, cause I don’t do violent movies or war movies, and that’s what I’d turned up to!

From the get go in this new feminist revisioning of Wonder Woman we are setup within the violence paradigm. A small Diana escapes the confines of her civilised day, moving from the city limits to the outskirts, where the women practice the art of fighting. At one level the geography can be seen as signpost to violence being the fringe of civilisation. But, this fringe-dwelling violence is where Diana yearns to be, and by extension it’s where the audience longs to be.

In social media sharing many women spoke of tearing up as the movie opened and for the first twenty minutes all they saw was strong, confident women moving with athleticism and ease as they practiced defence of self in hand-to-hand combat. Part of the feminist movement, for sure, has been about opening up all parts of life to women, including the armed forces. But another part of the feminist struggle has been to critique the premise of doctrines of just war, to posit that, fundamentally, a different way of resolving disputes is possible, one that doesn’t descend to violence.

Part of what bothers me about Wonder Woman is that violence and sacrifice seem to have a higher volume than love and negotiation. Friends point out that the sub-themes of love and negotiation are the radical component of the film, particularly love – not a common feature apparently. Also, the film does show the human/community impact of the European “theatre of war” in a way that mainstream war movies commonly gloss over, focusing on plot points in trench warfare rather than plot points played out in the destruction of villages and non-combatant lives.

Shane Claiborne, Enuma Okoro, and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove in their Liturgy for Ordinary Radicals share some truly wonderful words: “Peacemaking doesn’t mean passivity. It is the act of interrupting injustice without mirroring injustice, the act of disarming evil without destroying the evildoer, the act of finding a third way that is neither fight not flight but the careful, arduous pursuit of reconciliation and justice.”

And that, in a beautiful nutshell, is what troubles me about Wonder Woman. It’s been a few weeks that I’ve been ruminating on these thoughts so the movie is not entirely fresh in my brain. But I remember walking out with a dis-ease at the way the peace table had been manipulated by Ares as a plot twist rather than a legitimate process that led to the ending of the war. And I remember feeling frustration that sacrificial heroics by a man had, in this grand feminist adventure, been such a significant plot point.

On Friday, the UN adopted a Nuclear Weapons Treaty ban. Born from a campaign birthed in cups of tea in Melbourne. Hooray! But the treaty was adopted without the participation of Australia, the US and the EU. And there were some really dodgy gender messages that came out as US Ambassador to the UN, Nicky Haley, put forward the idea that “as a mother” it was her responsibility to ensure that the world had nuclear weapons, to keep us safe.

I don’t want to succumb to gender stereotypes that women are inherently peaceful and men inherently warlike. These ideas serve no-one. But I do think that it is useful to consciously consider the ways in which ideas of gender and militarism are tied together. To reflect on the way bodies marked as male and bodies marked as female, bodies marked by class and privilege, are used in the theatres of war: how working class men die and how women of all classes are raped. And I’m not really sure that Wonder Women challenged these dominant stories.

As I think about Nicky Haley and the Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty it is also useful to reflect on the ties of militarism, modern day politics, industrialism and capitalism. It’s hard not to notice, as someone who used to fly to Canberra regularly, the singularity of weapons and defence advertising at Canberra airport – doesn’t happen in Melbourne, Sydney, Perth, only Canberra.

Sitting at a peace table is hard work. Finding a way through the deeply held, oppositional ideas – the desire to walk away takes hold time and time again. We don’t often tell heroic stories about conversations. But we need to.

The stories we tell create the life we live. And when our stories set our aspirations for justice only as high as the most humane way in which to achieve slaughter, our aspirations undo our potential to conceive of a different way.

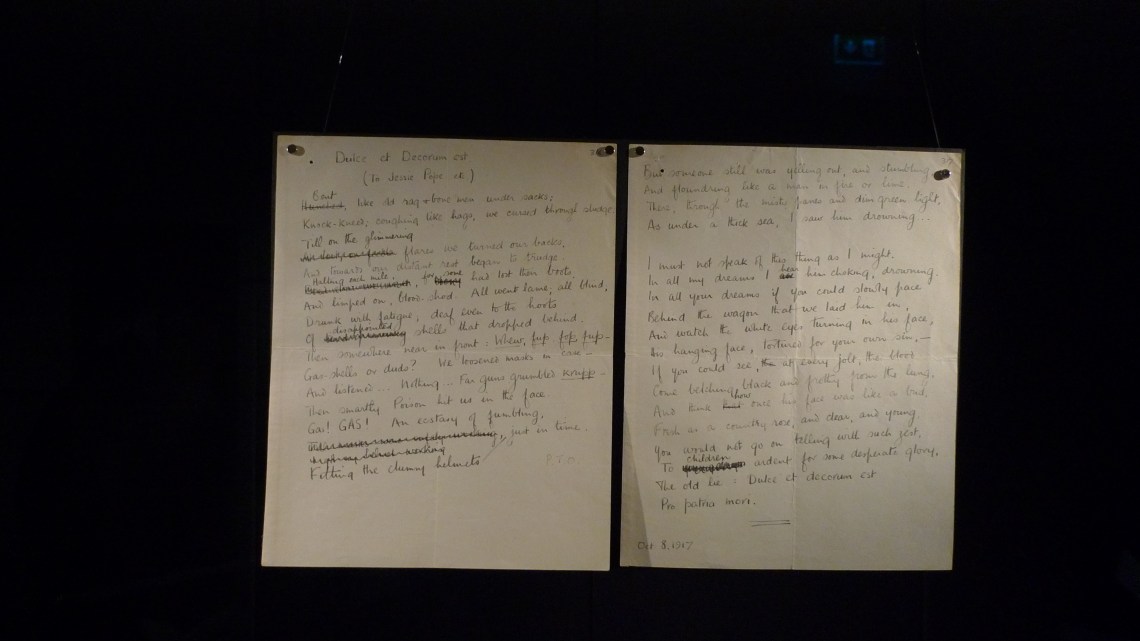

Wilfred Owen, in his beautiful poem, Dulce et Decorum Est challenges the “old lie” that it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.

Wilfred Owen, in his beautiful poem, Dulce et Decorum Est challenges the “old lie” that it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.

We talk of the art of war, crashing the brutality of slaughter into the breath-halting expression of beauty. Shouldn’t we rather talk about the art of humanity? That’s my Wonder Woman: embedding grace, love, justice and forgiveness into those stories that make myth the actions of our people.